![]()

‘Are my medicines really necessary’ is one of the most frequent questions from our patient led clinical education sessions.

In this blog Steve Turner, Head of Medicines & Prescribing @MedicineGov, reflects on the need to combine research and guidlelines with the patient’s actual experience, when deciding on medicines.

My experiences and learning

I was speaking about the use of medicines at a conference when I mentioned that medicines are ‘over prescribed’. Although nobody questioned and challenged me on this I was troubled by my use of this expression. By saying medicines are prescribed too frequently it seems to me this can be interpreted as a bad reflection on the prescribers.

As I mentally mulled this over (I’m not a quick thinker) I came to the conclusion that a beter expression may be ‘medicines are overused’. After all it’s us (the patients) who go to our Doctors, Pharmacists and Nurses and us who accept their prescriptions. Therefore if we agree that people can rely too heavily on medicines, and there’s wealth of evidence for this, then we need to sort this out together.

My social enterprise company’s Patent Led Clinical Education work came about because a large section of the population are prescribed multiple medicines, with potential for interactions and increased side-effects.

It’s widely accepted that 50% of the population don’t take their medicines as prescribed. Add to this the sometimes overlooked fact that people also use alternatives including over the counter medicines, herbal medicines , suplements, illicit drugs, self-medicate with alcohol, buy medicines over the internet, or borrow medicines from other people.

‘The human and financial costs of over use of medicines are immense. ‘

In our patient led clinical education sessions we have learned that many people don’t know what their individual medicines are for, and we see how many medicines are prescribed purely to counteract the side-effect of another medicine can pile up.

‘So far, nobody who has attended one of our sessions has expressed a wish to take more medicines, and those who did express a view all said that they didn’t want to take medicines if they didn’t have to.’

So what can we do together?

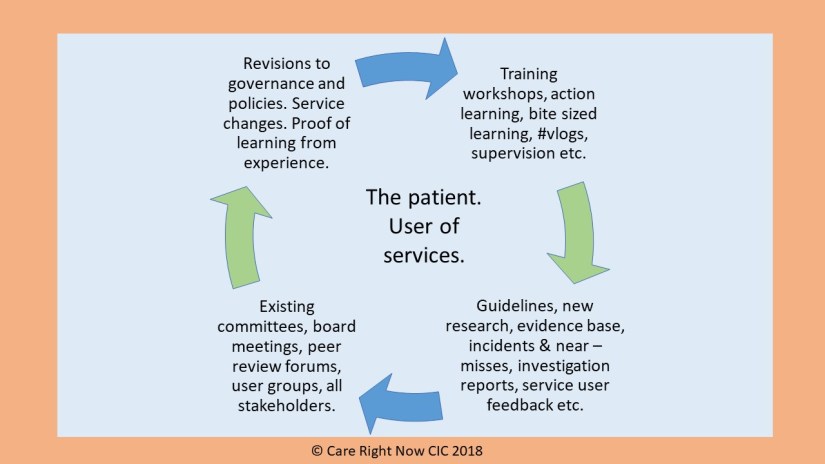

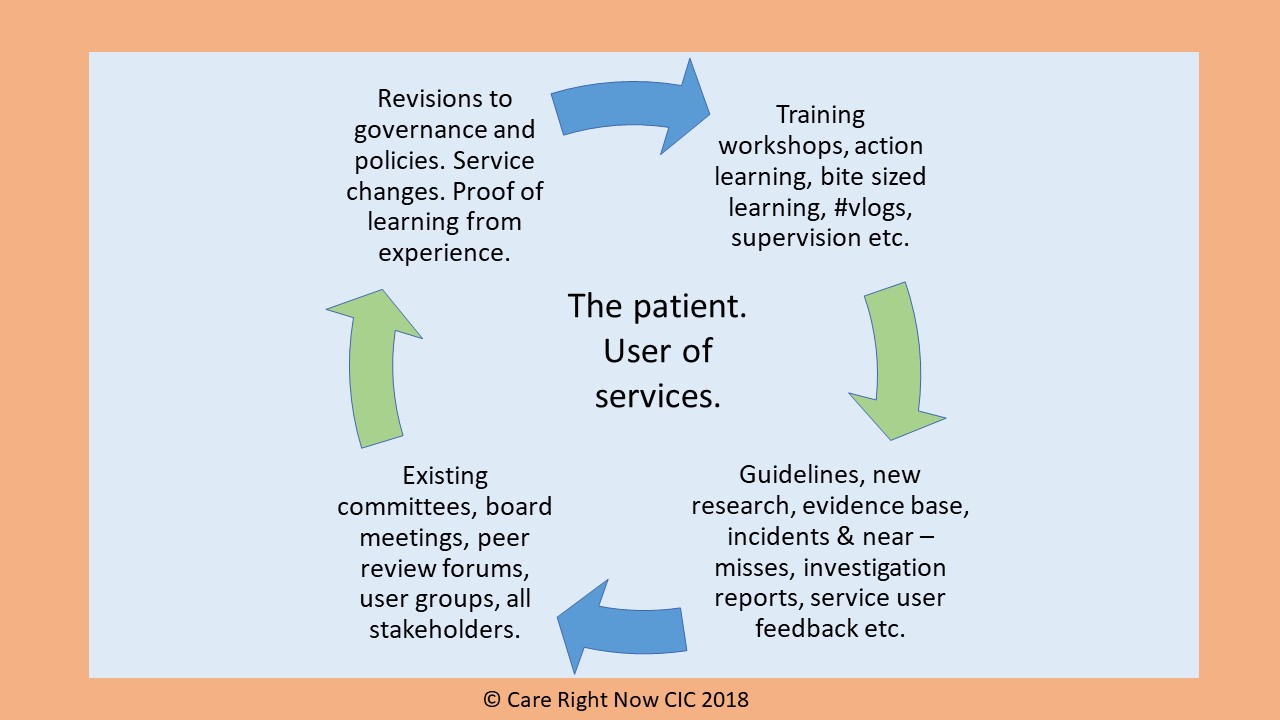

This blog aims to help us make sense of the vast amount of guidance available and describing why ‘trusted information’ is important in making decisions about medicines, and why this is only helpful if it it’s linked to the patient’s actual experience.

So much information, so many policies & guidance?

There’s an overwhelming amount of information and guidance on medicines, coming out on a daily basis. Even clinicians struggle to keep up and need help.

Two things are important in trying to make sense of this information overload.

- Making sure that the information you are looking at is from a ‘trusted’ source, (by this I mean ones that your prescriber is expected to use). see http://www.medsinfo.guru

- Linking this to patient experiences and support from others who have the same conditions.

- ‘Trusted’ information

The National Centre for Heath and Care Education [NICE] in England produces guidance, standards, indicators and evidence services covering health and social care. It’s not just about medicines. There’s a massive amount of trusted information on their web site, which covers:

- Conditions and diseases

- Health protection

- Lifestyle and wellbeing

- Population groups

- Service delivery, organisation and staffing

To get a feel for this one place to start is the NICE Pathways, where you can browse the topics, pick one and have the information presented in a diagram, where you can click on the headings for more information.

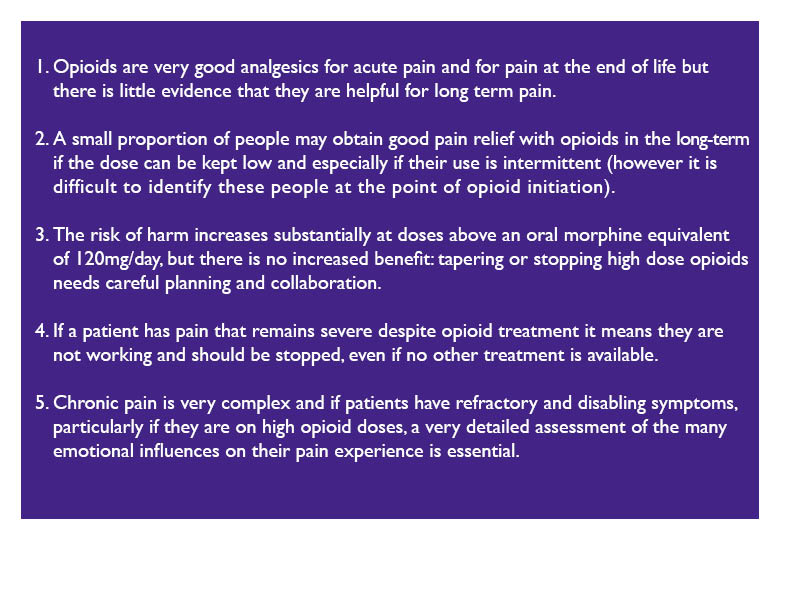

In some areas has been a move away from producing guidelines on a single illness or condition to a more holistic person based approach. This better reflects the complexities of real life, where it would often be a luxury to have just one illness with no complicating factors. NICE guidance on medicines optimisation, multi-morbidity clinical assessment and management, and patient experience in adult NHS services are good examples.

In addition NICE produces a document on Key Therapeutic Topics as part of the NICE Medicines and Prescribing Programme. This document is reviewed and refreshed annually. Click here for the topic list.

2. Patient experiences

Medicines (for adults) are tested and approved before that can be prescribed, and their safety is monitored, especially in the early stages, or if there are concerns (‘black traingle’ drugs). However drug trials are most often carried out on relatively small groups of people, usually from a limited range of ethnic groups, who who do not necessarily represent the population as a whole. For example, these ‘controlled trials’ usually exclude people with multiple illnesses, heavy drinkers or smokers, older people, and people with other illnesses such as addiction or mental ill health.

Controlled drugs trials are not carried out on children.

In addition the effect of medicines, including side-effects fall into two categories. Firstly, those that can be predicted (pharmaco-dynamic effects – that the effect of the drug on the body). Secondly, those that vary according to the bodily make up of the patient (called pharmaco-kinetic effects – the effect of the body on the drug).

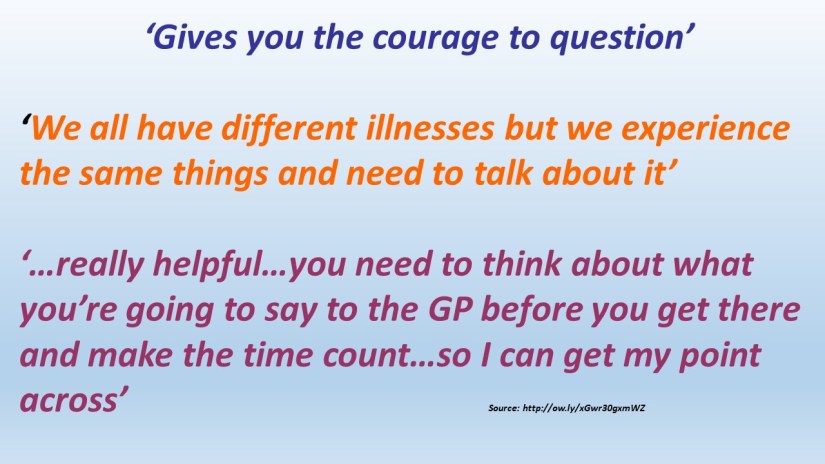

It’s only when you combine the guidance with the specific circumstances of the patient, including the ethnicity and physical make up and lifestyle of the patient that a decision on a medicine can be made effectively. For this to work, the patient must be part of this decision, and be allowed to lead on their own care. Our work shows this:

Testimonials on our patient led clinical education work.

Steve is a nurse prescriber, Head of Medicines and Prescribing for @MedicineGov , Associate Lecturer at Plymouth University and a former NICE Medicines and Prescribing Programme Associate.

info@carerightnow.co.uk

Author: Steve Turner

First published 1/8/2017 on http://www.carerightnow.co.uk . Last revised and updated 23/09/2021