Managing Medicines in Care Homes. Communication and sharing medicines information. Implementing NICE Guidance and Quality Standards.

Summary:

Steve Turner reflects on the communication challenges facing nursing and residential homes around implementing NICE Guidelines and Quality Standards and offers some practical advice.

Introduction:

Quality Standards on managing medicines in care homes from the National Institute for Health and Care Clinical Excellence in England (NICE) link to the NICE Guidance on Managing Medicines in Care Homes, which contains 118 recommendations.

This blog post offers suggestions on how to go about achieving quality standards, focusing specifically on communication and timely sharing of accurate medicines information.

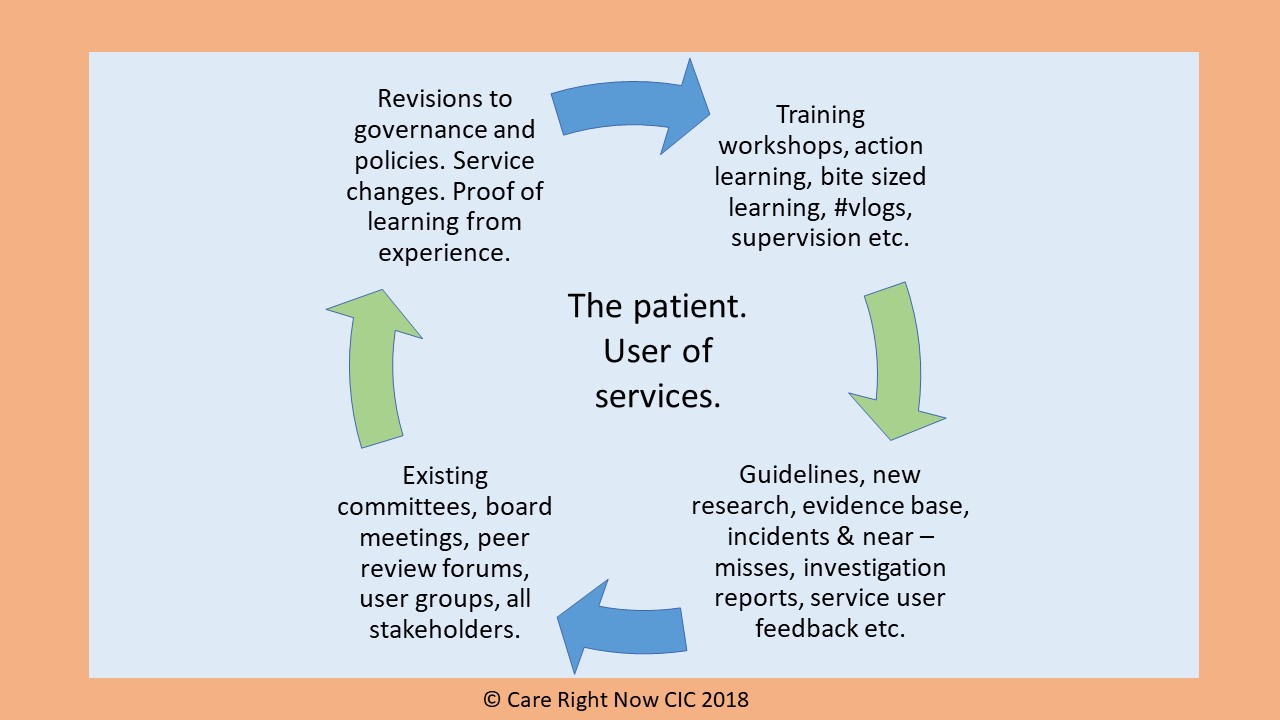

The findings are based on experiences of related quality improvement [QI] projects.

By working closely with front line staff in care homes, we have been able to identify and pilot some key changes. Then spread the learning.

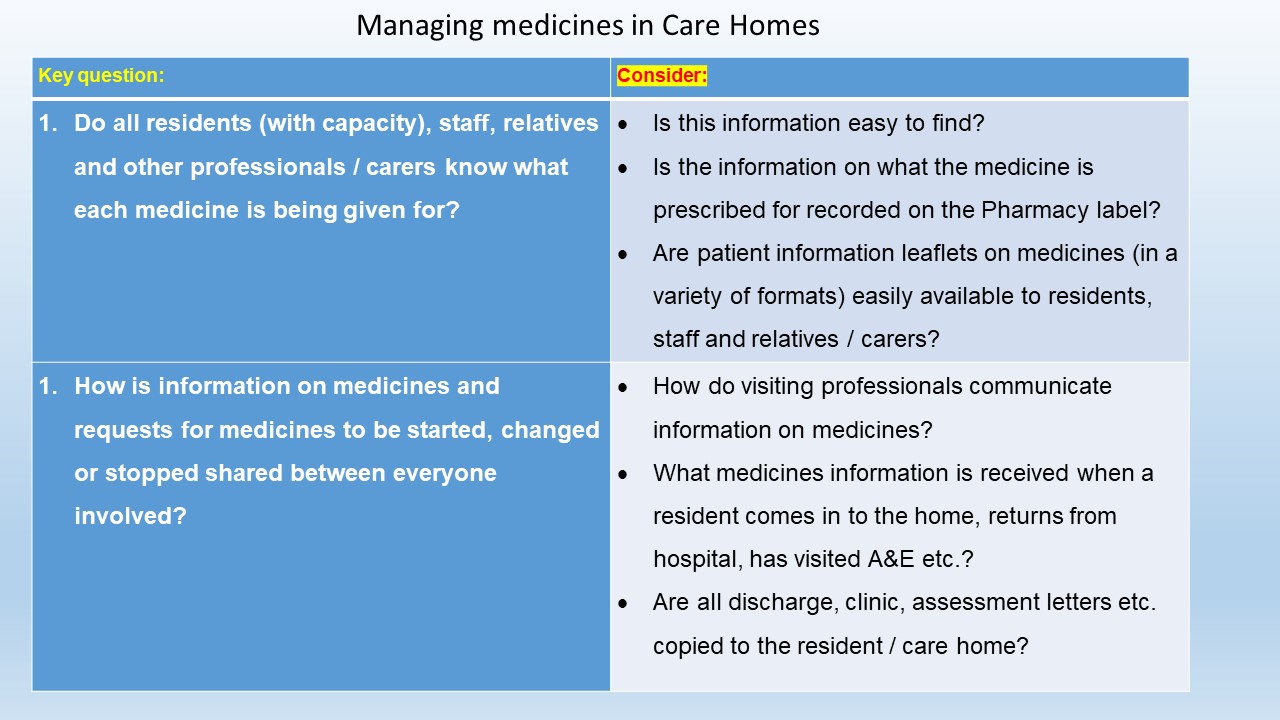

As part of this approach, we have produced an alternative checklist on managing medicine in care homes.

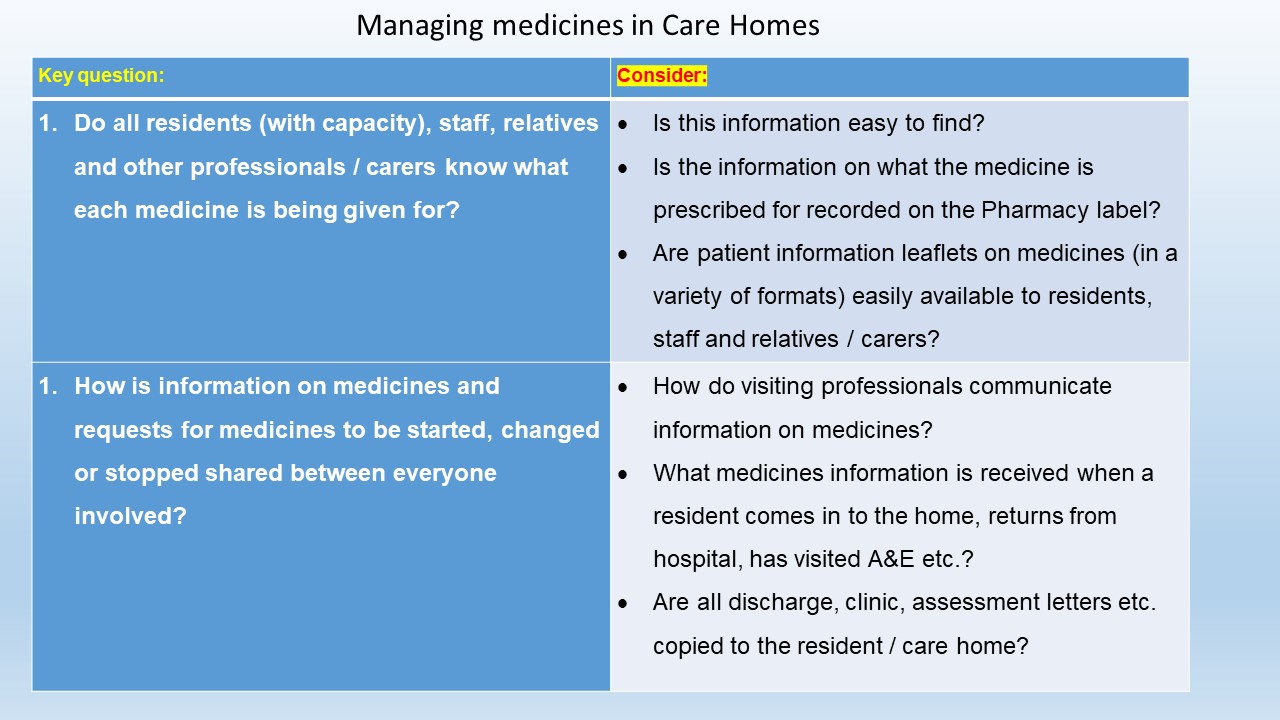

Managing medicines checklist:

By focusing on these questions at the outset, issues around best practice in medicines management can be identified.

These questions are particularly important due to the large number of people involved in the care of residents, which includes their G.P.; Specialist Nurses; Visiting Health Professionals; Pharmacists, Therapists, Hospitals and Outpatient Consultants.

Good quality management of medicines relies on all parties sharing information in a timely and auditable way. Much of this is outside the direct control of the care home.

Here’s two real life examples of things care homes can do to improve communication and promote best practice.

Example 1 – Knowledge of medicines and what are they being given for?

There are two principal areas to consider here.

Knowledge of medicines:

Firstly, how much detail should staff know about the medicines residents are taking?

There are many medicines which need to be given in a specific way, e.g. with food, before food, after food, dependent on the pulse rate etc.

Often more specific instructions apply, such as for alendronic acid, which is usually given for osteoporosis. These tablets must be swallowed whole and the person taking the medicine must remain upright for a period of time afterwards. This is because the tablet is acidic and will damage the stomach wall if it doesn’t pass through it quickly. So, if a resident is unable to take the tablet as directed, and therefore isn’t letting it pass through the stomach quickly, advice from a clinician as is needed straight away.

Another example of something where a basic knowledge of the medicine is needed is with the SSRI group of antidepressants (e.g., citalopram). Although these drugs aren’t addictive, they are medicines which need to be taken consistently and, if stopped abruptly (not tailed off), will often cause ‘discontinuation’ symptoms. These symptoms may include giddiness and very distressing feelings such as electric shock type sensations. If the resident is not able to express themselves easily their distress could be misinterpreted when they start to refuse to take it, or the supply has run out.

Information on each medicine is not always easily available. An answer to this is to ensure basic information leaflets on the medicines taken by residents are readily available to staff relatives and (wherever appropriate) to the resident, either in print, or online. A useful source of clearly written short medicines information leaflets is available at http://www.patient.co.uk .

Your local Pharmacy or Medicines Management Team, Specialist Nurses or G.P. will be able to give advice on the most appropriate patient information sheets, many of which are also available in easy read format and in other languages.

What are the medicines being given for?

Secondly, when giving out medicines, do staff, residents and relatives know what each medicine is being given for? NICE Guidance specifies that information on medicines and their indication (what they are being given for) should be readily available to all those involved in the management of medicines. In practice this isn’t an item which appears on most Medicines Administration Records (MAR charts). Neither is it always shown on the pharmacy label, which only lists exactly what the doctor has written on the prescription.

Why is this important? These differences can be significant, and lead to serious mistakes, if this information is missing.

Firstly, for completeness and safe care I believe it’s unacceptable not to have this information readily to hand. All patients (and / or those caring for them, and acting on their behalf), whether this is in a care home or the person’s home, should be given this information, in order that the person (or their representative) can be part of a shared decision-making process on the choice of medicines.

Secondly, visiting professionals and clinicians, out-of–hours and emergency services need to know this information to be able to assess and treat the residents safely. Many medicines can be given for different conditions often with a different dose range.

An example is amitriptyline which, if you look it up, is an anti-depressant; however, it is also given in lower doses for neuropathic pain, and sometimes used for irritable bowel syndrome.

Another example is lithium which is frequently prescribed as a mood stabiliser, it can also be prescribed, in particular circumstances, to enhance the effect of anti-depressants. Unless the reason for the prescription is known and easy to find things can go wrong. I have known clinicians to stop lithium inappropriately because the records were incomplete.

When working as a Community Mental Health Nurse I once visited someone who had attempted suicide, who explained that she was driven to it because she was taking an antidepressant and it ‘wasn’t working’. In fact, she had been prescribed amitriptyline for pain at a low dose, much lower than would be effective for depression.

In the longer term shared electronic medicines records are the most appropriate and robust solution. Prior to this, there are several things which will make the relevant information more readily available to all who need it.

At the risk of telling Granny how to suck eggs, here’s a checklist of interventions we are piloting as part of quality improvement projects:

1. Always query incomplete directions on medicines, either with the Pharmacy or the G.P.

2. When medicines are reviewed ask specifically for information on what they have been prescribed for, and record this.

3. Fax (or preferably email) medicines queries to G.P. Surgeries in order to keep a record of them. (This also means that people are not interrupted by ‘phone calls, don’t have to pass a verbal message on, and can consider the reply more fully.)

Example 2 – Records of communication between different services and professionals

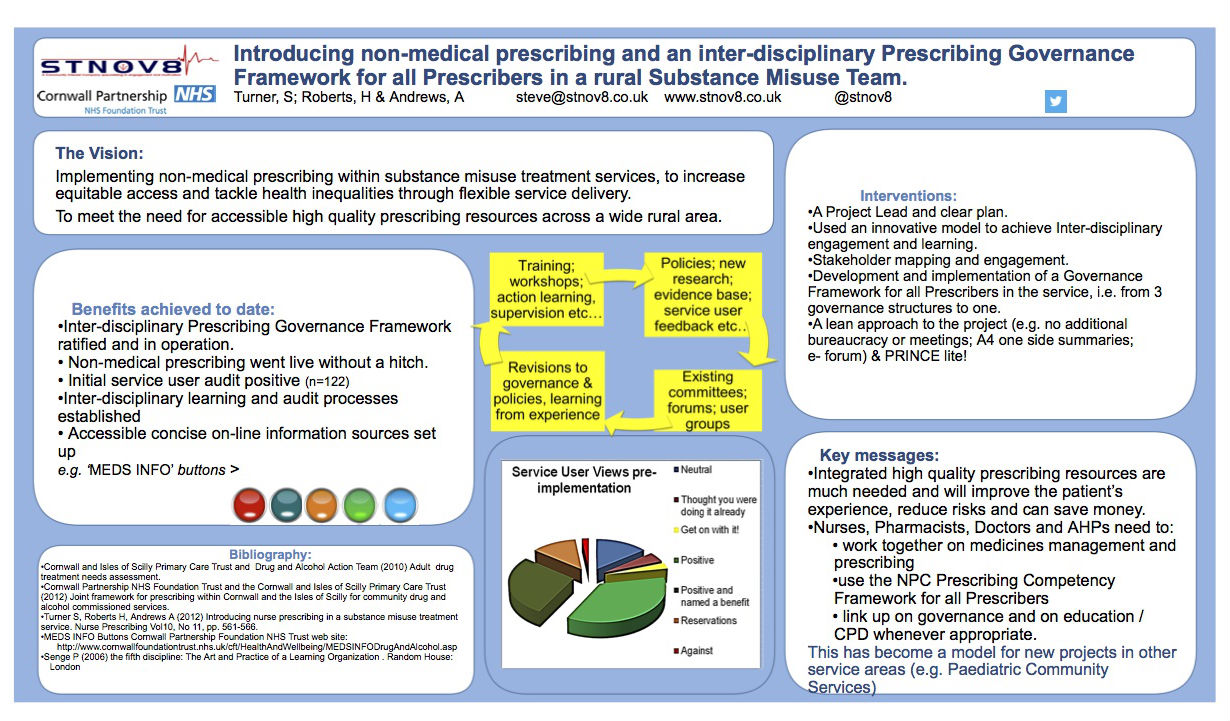

Residents medicines are often managed by several professionals, for example the G.P. may prescribe based on information from a Psychiatrist, Specialist Nurse, Physiotherapist, Speech Therapist, Dietician, or Non-medical Prescribers may change, stop or add medicines themselves when they visit the home.

Residents may also be prescribed a variable dose drug such as warfarin, where the dose is monitored and prescribed by a separate service. Some residents may also be seeing private clinicians, or receiving alternative therapies which need to be known to other prescribers.

Diets and dietary supplements too must be communicated to all prescribers, and this may have a significant effect on the absorption of medicines. The same is true for the resident’s posture, mobility, and state of hydration, so all clinicians need to be aware of problems in these areas.

Complex information about medicines is frequently recorded is a variety of places, and these records are not always complete, particularly when something changes outside of the standard review cycle.

We’ve been looking at this more closely with staff in homes as part of an action learning process, and came up with the following recommendations:

1. If discharge information on medicines is incomplete raise this with the hospital concerned in writing, and (especially if this happens repeatedly) and ask for information on what will be done to correct this problem in the long term. This need is reinforced by a patient safety alert issued by NHS England on ‘timeliness of communication with primary and social care when patients are discharged from hospital’.

2. When visiting professionals carry out an assessment and ask care home staff to contact the resident’s G.P., ask them to put this in writing. This avoids the possibility of mixed messages and enables a written record to be kept without duplication of effort.

3. When G.P.s visit the home to carry out reviews, prepare a structured written list of residents needing attention in advance of the visit.

Conclusion

Implementing Guidance and Quality Standards on medicines management in care homes can seem like a daunting task. By working closely with staff in the homes and starting out with some broad questions, things which need to be changed can be identified and worked through in a systematic way.

Many of the difficulties around communication lie outside the direct control of the care home, as a result communication and information sharing need to be looked at jointly.

Residents benefit from the homes taking a lead in insisting on full medicines information from prescribers, to ensure safety. This involves remaining steadfastly assertive in pointing out when information is incomplete.

- Key areas to focus on around communication are:

- Does everyone (residents, staff, representatives, and relatives) know what each medicine is being given for?

- How are changes to medicines (i.e. starting, stopping, dose alterations and requests for reviews) communicated?

Version 3 . Updated: 21.03.2022